context

serena lee

affinities

practice

Now that you're here,

take off your shoes, take off your coat,

let go of your bag,

let go of the things you carried in.

Now that you're here, let yourself sit, let yourself sink.

Feel yourself sink,

Notice your pace

Notice how the ground feels

Breathe in,

expand,

a feeling of horizon

Breathe out,

sink,

without intention

Do it again

Doing, again, you are in between

Notice it happening

Notice things changing with time

how slow, how small

Inside of you, outside of you

What you think is the centre, changing

What feels like the centre, changing

moving through, moving around, moving with, moving within,

Notice the question, what does this do?

Notice the question, what should I do?

Notice what you are carrying

Remember to notice

January 15, 2022. Performance. Su Feh.

Witnessed by Kristen Lewis and Niki Kihira.

We, whoever we are, are two, at least for now.

We take off our shoes, replace them with the plastic and foam slippers they have provided. They are too big but my feet do not mind the chance to take up more space than usual. Silent, we shuffle over to what seems to be the threshold. We cross a path made of fresh woodchips, laid out on the inside floor. We need to duck down a little, so that we do not disturb the curtain of Eucalyptus, drying overhead—extraordinary its smell, if you get close enough and your nose knows what to look for.

We step through a circle gateway, a second threshold, in a way cervix to the first threshold’s wider opening, lifting our feet to avoid the rows of carefully placed juice-packs, full of factory-issue Chinese tea, guarding the entryway. But that is not quite true: there was another way through and so the juice packs did not guard the entryway but simply a entryway. And, too, they invited us to cross over, so they were more host than guard, though one can serve both functions.

All around, sheer, white fabric like clouds hangs from the ceilings, creating a small alleyway between actual wall and curtain-wall. The curtains are the kind my mother used to have on her living room windows; like a good boundary, substantial enough to block the intrusive gaze of passersby on our busy downtown street but porous enough to let the winter light in. We are enclosed on 3 sides by this curtain-membrane. Behind it soft white lights dance. In the middle of this small room, the sound of water indicates a fountain whose form is suggested by small mountains of foil, carefully arranged.

In between the curtains and the walls, in the thin, alley-like space of in-between-ness, she dances. You hardly see her at first but know without looking that she is there—and not only for the mundane reason that you are here because she is, that her dancing is the reason for your having arrived here, wherever you are, whoever you seem to be in this moment. No, you know she is there by the way the space moves with her. The white curtains ripple slightly, yes. A hand or foot appears through them—yes, also that. But more than that—the space invisible also moves with her, light as clouds but solid, down-coming. You can feel, if you listen: the sides of you open, wrap around and beyond you, making for you space in the same way she is making space for this place.

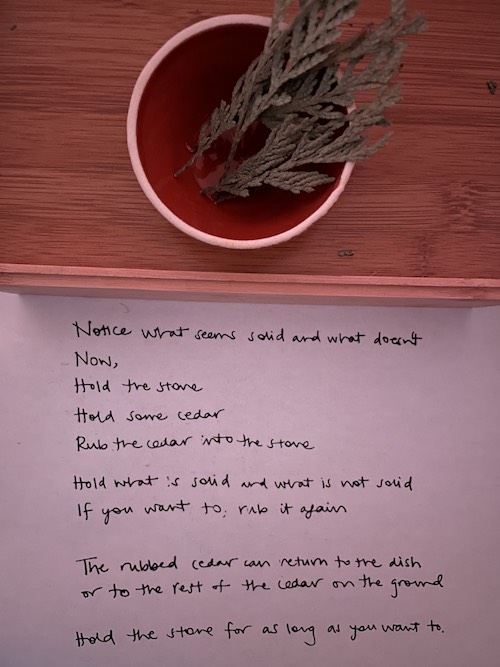

Tactility comes live inside me in this space; I can, without moving and without effort, hold and brush and feel space more completely here. We sit down on two cushions between which a bowl of cedar sits, and with it an instruction to take stones into our hands. My fingers remember suddenly every time I have ever crushed cedar between them--felt it sting and cut me gently, let its smell become me, for a time.

There are, yes, two of us in here as witnesses, for now; no other human audience. We sit quiet, cross legged on the floor, the cedar between us and the Eucalyptus just across the way. Wrapped in curtain-clouds, with the sound of water all around us, I remember that space can be made anywhere but it takes a maker. It takes a body to dance space into being; a body to see how space will and could be made.

To sit there and be still, while space is made, is a great and subtle privilege—to witness time unwinding, to not have to see completely, to know dance by the traces it leaves in the mind of space, more so than by how much it lets us “see.”

We slip out as quietly as we came, find ourselves again in the bustle of Chinatown on a Saturday afternoon, remembering more closely the play and labour of the invisible within the visible, and all the silent work that slips between the cracks of the known, making other worlds possible, while we, whoever we are, wait—and, if we are lucky, learn to feel our hands become at once light as clouds and heavy as stone, feeling the weight and lightness of all the work, the better part of it always unseen, that goes into the making, the weaving, the holding of space, however provisional.

We, the two recent witnesses to the dance, round the corner, the gallery receding in time and space. My companion selects dried squid from one of many bins full of too many good things to count; I pick out some Morel mushrooms, which remind me of a certain grove of Oak trees where, long ago, I found them wild one day in early spring. We chew on the tough, salty squid and talk about a possible soup-to-come. He says to me, “you know, that dance, it was like being inside the idea of a Chinese garden.” He is Japanese and grew up in Tokyo and between there and his not infrequent trips to China as a child and teenager, he carries in him several ideas of ‘Chinese Garden.’ “We could have gone over there” (he gestures with his hand in the general direction of a Chinese Garden he knows to be nearby in the neighbourhood) “but instead they made this one inside, out of juice boxes and tin foil. Interesting.”

He studied Japanese Tea Ceremony in his youth, before migrating to Canada. He speaks to me about the ceremony with some frequency, and displays its principles in the careful way he sets up, often without realizing it, ordinary moments so that they become containers for the beholding of a beauty that skirts the line between seen and not. His presence at the dance this afternoon reminds me that, some weeks before, I had heard Su Feh speak in a conversation hosted by the Dance-in-Vancouver 13th biennial called “Making Ceremony.” I do not remember everything about that conversation, but I do remember Su Feh saying that the Chinese tea ceremony is different from the perhaps better-known Japanese tea ceremony, in that the Chinese version tends to be less ostensibly formal, that it makes use of what is at hand.

Remembering this, now, with this garden the artists, in my friend’s words, “made inside” now come inside me as memory, I consider the obvious: that we make ceremony as we need to, with what is close at hand, improvising as we need to out of the stuff our nature-culture both gives and takes away. And ceremony makes us, too. Flip flops and cedar; eucalyptus and tin-foil; clouds and my mother’s curtains; gardens and manifold ideas of gardens; the difference between that ceremony and this one, the dance that came before and the dance we behold now—all form relations in this space animated by the dancing that goes mostly unseen. This hidden dance, as provisional ceremony, connects, however tangentially, the through lines that divide us. It invites, if we let it, a wider, softer way of seeing.

Kristen Lewis, JD is a dancer, writer, performance artist, and movement educator. In all of these overlapping and intersecting roles, she is interested in how the beauty and intimacy of embodied, land-based approaches to movement and storytelling can open up information-saturated Human Persons to something of the experience we lose when we forget our emotional, sensory, animal selves and neglect the wider circle of relations that ground us in the places that hold us and make us.

My name is Daisy Kim, a third year student of Emily Carr University of Art and Design, majoring in Industrial Design on an endeavour to nourish and exercise my design knowledge in any way possible. I value purpose and personal progress over skillsets or outcome. I approach my design practice in that manner.

wave hands,

like clouds,

not eyes

Fall 2021 - Winter 2022

Or Gallery, Vancouver, Canada

curated by Denise Ryner

with:

Lee Su-Feh

Megan Hepburn

Gina Badger

Justine A. Chambers

Katrina Goetjen

Jordan Milner

Trevor Discoe

Kitt Peacock

Produced with the generous support of the Canada Council for the Arts

Not unlike the classical Chinese garden down the street from Or Gallery, you enter in the midst of movement, of processes, of circulating elements, of tones struck and resonances ebbing,

Not unlike the opening of a taijiquan form, you start by noticing the ground,

you are drawn in, to traverse soft and hard,

you forget to notice,

you remember to notice

as you move,

as you pause,

Not unlike the spas you're familiar with, passing through relaxation, intimacy, 'natural', intention, attention,

We notice time,

how we experience time in the space.

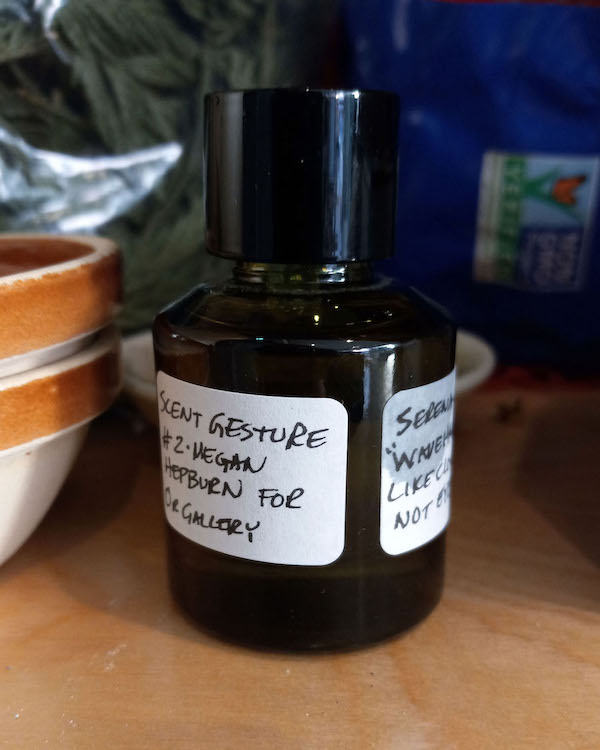

We attune ourselves to time with 'scent clocks' -- a changing menu of scent gestures created collaboratively with Megan Hepburn and Gina Badger.

We notice time, how things initiate and fade,

carrying incense with us,

rubbing fresh cedar sprigs,

holding warm stones as they cool,

peeling clementines,

stepping on cedar,

diffusing vapour,

infusing brew,

watching smoke,

brushing eucalyptus

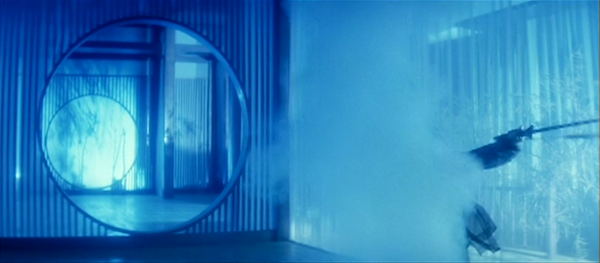

What you see here are images of wave hands, like clouds, not eyes at Or Gallery: exhibition documentation by Dennis Ha; scent gestures in process and as they are encountered in the space documented by Gina Badger and Megan Hepburn.

You also see images of Lee Su-Feh engaging with the space, waving hands like clouds, documented by Reiko Inouye.

You can read Kristen Lewis's writing on her experience of visiting the space with Niki Kihira, witnessing Lee Su-Feh's movements.

You can read Daisy Kim's description of her experience of the space as a narrative.

You can also read prompts for noticing and engaging that guide guests through voice and handwritten notes.

You also see images that have helped to shape the space, gathered through visits, conversations, wuxia films, and disparate moments.

Among them:

The painting of 七星岩 (Seven Stars Crags) is in my grandparents' living room, it was painted by an artist at Gerrard Square Mall in Toronto, based on a photo spread in a 1970s Chinese tourism magazine, commissioned by my grandfather Tin Lee; he calligraphed the title in the bottom right corner.

The photo of the juice box airplane under construction in a Chinese supermarket in the UK was sent to me by Giles Bailey in 2016.

You see images of the Dr. Sun Yat Sen Classical Chinese Garden in Vancouver, and other mountains in the Royal Ontario Museum's collection in Toronto.

What you don't see, but rather hear, is the 古琴 gu qin / gu kam (ancient stringed instrument.)

And the sound of water.

With you, in the space, at different times:

eucalyptus sprigs,

digital photos printed onto fabric curtains hung from a steel hoop,

cedar chips from Megan's neighbour, on Squamish (Sḵwx̱wú7mesh) territory

sound installation of 古琴 gu qin

incense cones (Sandalwood; Agar; Megan's blend: Cedar, Fir, Fir resin, Frankincense carterii, Gum Arabic, Jasmine grandiflorum, Makko, Osmanthus, Sandalwood, Vetiver and Rose water)

essential oils and aroma diffuser,

mountain backflow incense burner made with salt dough and ink

polyester, chiffon sheers,

LED lights,

reflective mylar,

water,

aquarium pumps,

a moon gate made with painted pine, 維他檸檬茶 Vita Lemon Tea juice boxes

straw mats

palm-sized stones from the beach

clementines

cedar sprigs from Gina's front-yard trimmings on K'ómoks territory

brewed and burned full-moon harvested mugwort flowers from Gina's garden

With me, in the space, thank you:

Tin & Eileen Lee

Shing Gip Jan

Joan Jan

Philip Lee

Alix Eynaudi

Christie Pearson

Christina Battle

Fan Wu

GG

Giles Bailey

Karen Tam

Lee Su-Feh

Leonardiansyah Allenda

Sameer Farooq

Toby Reid

Yam Lau